QNX From The Board Up #10 - Kernel Initialization, Part 2

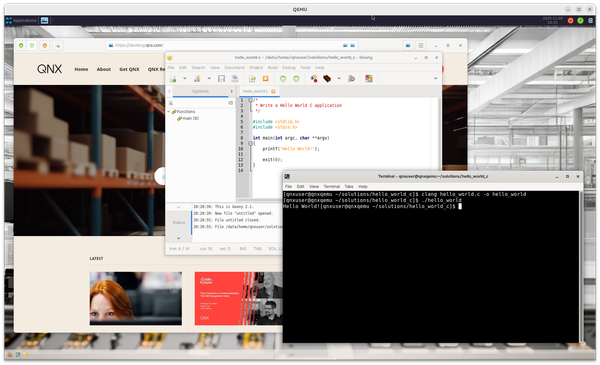

Enjoy this quick detour from our regularly-scheduled program for a (fun!) look at inspecting the kernel (and other processes) to see exactly what's running and how they are communicating.

Welcome to the blog series "From The Board Up" by Michael Brown. In this series we create a QNX image from scratch and build upon it stepwise, all the while looking deep under the hood to understand what the system is doing at each step.

With QNX for a decade now, Michael works on the QNX kernel and has in-depth knowledge and experience with embedded systems and system architecture.

Quick Detour: Visual Confirmation Of Kernel Initialization

Last time we talked about kernel initialization.

This is going to be a quick detour before we look at mmap() to poke around the freshly initialized QNX kernel and see if we can see some of the things that we were talking about in the previous article. (Spoiler: Okay, maybe not so quick!)

For this, I'm going to use the extremely powerful tool that I've briefly alluded to before, pidin, which lets you look at information about pids, i.e. process ids.

For our extremely (too?) minimal configuration, it means we can use pidin to make sense of everything that's going on, based on our understanding of what we've discussed in these articles so far.

Note: For this article, I'm using kkissh, the kilo KISS shell, which is really just nkiss (nano KISS) with:

- a prompt that includes current working directory, and

- support for backspacing, because lack of this was reeeeeeally a pain. I'm not a prefect typor.

How to use pidin

The documentation for pidin is thorough, but I'll also point out another utility, use which is kinda like man in that it prints out a short manual for a utility.

How do you use use? Let's ask it by adding use to the build file for our image

useand then run it on itself:

/ # use use

use - print a usage message (QNX)

use [-aer] [-i|-s] [-d <directory>] [-f <filelist>] files

Options:

-a Extracts all usage information from the load module in its source

form, suitable for piping into usemsg.

-d Recursively display info for all files under <directory>.

-e Only consider ELF files.

-f Read list of files, one per line, from file <filelist>, displaying

usage info for each.

-i Displays information from load module (ELF only).

-s Displays .ident strings (ELF only).

-r Displays information about running process and libraries (native only).

-q Displays .QNX.command.line section

Where:

files A list of executable load modules or shell scripts that contain

usage messages (see printed documentation for use and usemsg

for details).Where does use get the information about a program? From the program itself!

If, on the Ubuntu box I use, I go to the SDP directory, and look for the use utility:

sdp $ find . -type f -name use

./target/qnx/x86_64/usr/bin/use

./target/qnx/aarch64le/usr/bin/use

./host/linux/x86_64/usr/bin/useI see one for QNX x86_64, one for QNX on aarch64le, aka Armv8-A 64-bit, and, oh, one for linux too! Interesting.

And if I then look at the insides of the ELF file we loaded onto our QEMU x86_64 target with the readelf utility, we'll see:

bin $ pwd

/home/mtb/sdp/target/qnx/x86_64/usr/bin

bin $ readelf -SW ./use

There are 30 section headers, starting at offset 0x149b8:

Section Headers:

[Nr] Name Type Address Off Size ES Flg Lk Inf Al

[ 0] NULL 0000000000000000 000000 000000 00 0 0 0

[ 1] .interp PROGBITS 0000000000000200 000200 000017 00 A 0 0 1

blah blah blah

[24] QNX_usage PROGBITS 0000000000000000 01174d 000326 00 0 0 1

[25] .gnu_debuglink PROGBITS 0000000000000000 011a74 00000c 00 0 0 4

[26] QNX_info PROGBITS 0000000000000000 011a80 0000e9 00 0 0 1

blah blah blahA section named QNX_usage that is 0x326 bytes. Is that about right? We saw above that we can use use on Ubuntu too, so let's try something:

bin $ use use | wc -c

809

bin $ printf '0x%x\n' 809

0x329Close enough for jazz. Those three bytes, and QNX_info? I'll save that for a whole article on use. Back to the original detour.

Processes

We said there's a kernel process, and then once the kernel process is initialized, a thread in the kernel process runs the commands in the init script, which for us is this:

[+script] init = {

procmgr_symlink /proc/boot/ldqnx-64.so.2 /usr/lib/ldqnx-64.so.2

PATH=/proc/boot /proc/boot/kkissh

}i.e. run our bare bones "shell", kkissh, with the environment variable PATH set. So there should be 2 processes: kernel process and kkissh.

Let's ask pidin to show us what processes are running.

According to the docs, this seems to be the parameter we're looking for:

arguments (equivalent to -F "%a %A")

Show the arguments of the displayed processes.arguments is a lot to type. Can't I just type in a few letters? Enough to be unique?

/ # pidin ar

pid Arguments

1 procnto-smp-instr

2 kkissh

3 pidin arIt seems I can.

- pid 1 is called

procnto-smp-instrbecause that's the name of the binary the process came from. It's the kernel process. - pid 2 is our little program / shell,

kkissh. - pid 3 is

pidinitself, which was running at the time it queried the QNX kernel for the list of currently-running programs.

Channels

We said that the kernel process, pid 1, has a channel, and all the processes have a connection to that channel.

Let's see that channel using the channels argument to pidin:

/ # pidin channels

pid tid name

1 1 /proc/boot/procnto-smp-instr

00000001: flags 0000200a PulseQ 0 SendQ 0 ReceiveQ 6 ReplyQ 2 Type -

1 2 /proc/boot/procnto-smp-instr

1 3 /proc/boot/procnto-smp-instr

1 4 /proc/boot/procnto-smp-instr

1 5 /proc/boot/procnto-smp-instr

1 6 /proc/boot/procnto-smp-instr

1 7 /proc/boot/procnto-smp-instr

1 8 /proc/boot/procnto-smp-instr

1 9 /proc/boot/procnto-smp-instr

1 10 /proc/boot/procnto-smp-instr

1 11 /proc/boot/procnto-smp-instr

1 12 /proc/boot/procnto-smp-instr

2 1 proc/boot/kkissh

12291 1 proc/boot/pidinSo, pid 1, the kernel process, has a channel with an id of 00000001. (There is no 0x prefix, but, it is in hex.)

pidin reports the channels for the process after it reports the first thread.If, for example, you were to create a process with 2 threads, and each thread creates a channel, you'd see something like this:

/ # pidin -p 4100 channels

pid tid name

4100 1 proc/boot/2channels1perthread

00000001: flags 00000000 PulseQ 0 SendQ 0 ReceiveQ 0 ReplyQ 0 Type -

00000002: flags 00000000 PulseQ 0 SendQ 0 ReceiveQ 0 ReplyQ 0 Type -

4100 2 proc/boot/2channels1perthreadWe said that each process has a connection to the kernel process's public channel. How can we see that?

First, for this information to make sense, we'll have to back up a bit.

Background: Connections

In previous posts about message-based IPC, we said:

ConnectAttach()is used to create a connection to a channel.- it returns a connection id

MsgSend()(et al.) is used to send a message over a connection to a channel.- Depending on the types of messages used, a connection is either:

- a connection, or

- a file descriptor

- when using QNX-specific POSIX-file functionality messages, e.g.

_IO_WRITE

- when using QNX-specific POSIX-file functionality messages, e.g.

But, it's not just about the messages sent. There's another distinction to make, and it has to do with the value of a connection id:

- one range is for connections, and

- one range is for file descriptors.

There's a good reason for this.

File descriptors are fundamental to UNIX and UNIXy OSs, and, therefore, like in bowling, there are rules. POSIX and UNIX history impose certain rules regarding what values file descriptors must have. One of those rules: file descriptor values must start at 0, and increase from there.

As a result of this rule, QNX uses:

- one range of values for connection ids starting at 0 for file descriptors, and

- one range of values for connection ids starting at

_NTO_SIDE_CHANNELfor "regular" / not-a-file-descriptor connections.- This is also referred to as "a side channel connection", aka "a side channel".

Yes, it is confusing to call a connection to a channel a "side channel"; a "side channel" in QNX is not some kind of funky channel.

The terminology stems from the telecommunications sense of a main channel of communication versus a side channel (non-main channel).

I like to think of it in a restaurant context. Customers come and go through the main front door. However, activities essential to keeping a restaurant business running, but needn't be of concern to customers – things like food deliveries and smoko -- happen at the door on the side of the restaurant.

Most communication over connections in a deployed QNX system will be via file descriptors. Therefore any communication not done via a file descriptor (fd) is a "side channel".

Connection Id Ranges

Let's look at these connection id ranges.

ConnectAttach() returns a connection id as an int. How big is an int? QNX 64-bit is LP64, and therefore ints are 32-bits.

Let's check that:

printf("sizeof(int) = %zu\n", sizeof(int));prints:

sizeof(int) = 4Although not required by the C specification until recently, QNX uses two's complement representation for integers. One nice thing about two's complement is that the most significant bit (MSB) indicates whether the value is negative (MSB set) or positive (MSB clear).

Summary: a connection id is a 32-bit signed integer represented in two's complement.

Given that, if we run this code on QNX:

printf("%d, 0x%X\n", _NTO_SIDE_CHANNEL, _NTO_SIDE_CHANNEL);we get

1073741824, 0x400000000x40000000 does not have the most significant bit set, therefore that means that connection ids for side channels are positive integers. But, they are honkin' huge ones. We'll come back to this.

Quick recap of this background info before we move on:

- Connection ids are 32-bit signed integers, two's complement

- A file descriptor is a connection

- File descriptor values start at 0

- A side channel is a connection

- Side channel values start at

_NTO_SIDE_CHANNEL(0x4000'0000)

- Side channel values start at

Connections

We're back to wanting to see the connection that each process has to the kernel process's channel.

According to the pidin docs, fds is the parameter we need:

fds (equivalent to -F "%a %28n %o")

Show information about the process's connections and file descriptors.Let's see:

/ # pidin fds

pid name

1 /proc/boot/procnto-smp-instr

0s 1 <procnto>:1

2 proc/boot/kkissh

0 1 rw 0 /dev/text

1 1 rw 0 /dev/text

2 1 rw 0 /dev/text

0s 1 <procnto>:1

16387 proc/boot/pidin

0 1 rw 0 /dev/text

1 1 rw 0 /dev/text

2 1 rw 0 /dev/text

3 1 <procnto>:1

0s 1 <procnto>:1kkissh

Let's first take a look at our "shell"'s fds info:

2 proc/boot/kkissh

0 1 rw 0 /dev/text

1 1 rw 0 /dev/text

2 1 rw 0 /dev/text

0s 1 <procnto>:1Process 2, kkissh, has 4 connections. The first 3 are 0, 1, and 2. Those are in the file descriptor range, so those are file descriptors. In fact, they're the standard fd numbers usually given to a process:

| fd Number | Macro | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | STDIN_FILENO |

Standard input |

| 1 | STDOUT_FILENO |

Standard output |

| 2 | STDERR_FILENO |

Standard error |

Let's look at "standard input" in detail:

0 1 rw 0 /dev/text| Info | Description |

|---|---|

0 |

The file descriptor value. |

1 |

The process id of the process the connection is to. |

| (1 is the pid of the kernel process.) | |

rw |

Flags passed to open(). This means O_RDWR. |

0 |

The offset into the file. |

/dev/text |

The name of the file or device, if available. |

/dev/text is exactly what we expect! In an earlier article we talked about how that is the file:

- exposed by the kernel process's resource manager that uses the startup's debug callouts, which, in our QEMU configuration, make use of an 8250-esque UART, and

- initially used for standard input, standard output, and standard error when a process is created by the init script.

So, being a connection to the kernel process (1) makes sense. We saw earlier that the kernel only has one channel, so, that's the one.

Aside: rw?

rw for standard input? Shouldn't that be r-, i.e. read-only?

It is my unsubstantiated belief that this is for "historical reasons" stemming back to the days of "It's a UART. Of course you can read and write!"

Yes, you can write() to STDIN_FILENO, and the results are the same (AFAICT) as if you had used STDOUT_FILENO. Terminal tomfoolery!

However, the C FILE* stdin, which makes use of STDIN_FILENO, is created (from scratch) to be read-only. Therefore, if you try to write to stdin with, say, fputs() or fprintf(), you will be given an error. Which error? EBADF, "Bad file descriptor", which is rather misleading because it's a perfectly good fd to which one may write.

Why the error? The FILE (a struct) for stdin was created with some flags that say "You were opened read-only. Trust me." but, the fd placed into the FILE was open()ed O_RDWR. The code in fputs() and fprintf() checks the flags in the FILE to ask "Were you created in a way that supports writing?" and the flags say, "No." Alright, here's your EBADF.

Very Aside: Caveat Programmor

But, if I use the full-featured shell, ksh (Public Domain Korn shell), which comes with the QNX SDP, plus a proper serial driver, devc-ser8250, so we have job control (three topics I have purposely been avoiding so as to not muddy the waters), and then do something like this which changes the 3 standard file descriptors to refer to non-serial-driver files:

/ # sleep 1000 < /dev/zero > /dev/null 2>&1 &

[1] 4100

/ # pidin -p 4100 fds

pid name

4100 proc/boot/sleep

0 1 r- 0 /dev/zero

1 1 -w 0 /dev/null

2 1 -w 0 /dev/null

0s 1 <procnto>:1(I chose sleep because it's very good at doing nothing. This isn't about sleep.)

Read-only for standard input, write-only for standard output, and ditto for standard error. Now that's more like it.

So, don't always assume in your program that you can get away with terminal tomfoolery. You have no idea how someone has run your program and set up the fds. (Well, you can ask. But don't assume).

Back To The kkissh Connections

That's the first 3 connections understood: file descriptors. Standard file descriptors, all to /dev/text, a file exposed by a resource manager running the kernel process, pid 1.

Now for that 4th and last one:

0s 1 <procnto>:10s?! What is that?

According to the pidin documentation, the argument "fds" is the same as -F "%a %28n %o", where

ameans display the process IDnmeans display the process path (padded/truncated to 28 characters)omeans display the connection IDs and file descriptors associated with the process

The information for o goes on to say: "the file descriptor, followed by s if it's a side channel" (emphasis mine)

Ah! So pidin is using a shorthand for those honkin' huge connection ids for side channels!

- The 0th side channel,

_NTO_SIDE_CHANNEL, i.e.0x4000'0000, is represented as0s. - The 1th side channel,

_NTO_SIDE_CHANNEL+ 1, i.e.0x4000'0001, would be represented as1s.

(And, since most people are mostly using file descriptors, and therefore most interested in file descriptors, the pidin command is called "fds" and not "connections".)

Let's dig into these fields:

| Info | Description |

|---|---|

0s |

the 0th side channel, i.e. connection id 0x4000'0000

|

1 |

the id of the process the connection is to, i.e. 1, the kernel process |

<procnto>:1 |

The name of the process 1, procnto, aka the kernel process |

and the channel id, 1. |

There it is! This is the connection / side channel that all processes have to the kernel process.

You can see it there for pidin too. And, the kernel process too. We mentioned last time that part of the kernel process's initialization, after creating its public channel, is to create this connection (side channel) to itself, because it's "just another process", at least in this regard.

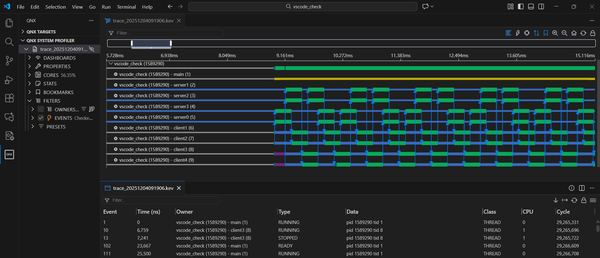

Threads

We said that the kernel creates threads in the kernel process:

- an idle thread (one per CPU),

- then I added a mysterious ellipsis (...),

and that the kernel process itself then creates a thread pool for the servers (e.g. Memory Manager) and resource managers (e.g. /dev/text).

Let's take a look and see what pidin can tell us with the threads argument:

/ # pidin threads

pid tid name thread name STATE Blocked

1 1 /proc/boot/procnto-smp-instr idle_cpu_0 READY

1 2 /proc/boot/procnto-smp-instr ipi_cpu_0 INTR

1 3 /proc/boot/procnto-smp-instr clock_cpu_0 INTR

1 4 /proc/boot/procnto-smp-instr sched_sporadic NANOSLEEP

1 5 /proc/boot/procnto-smp-instr thread_reaper SEM 0

1 6 /proc/boot/procnto-smp-instr 6 RECEIVE 1

1 7 /proc/boot/procnto-smp-instr 7 RECEIVE 1

1 8 /proc/boot/procnto-smp-instr 8 RECEIVE 1

1 9 /proc/boot/procnto-smp-instr 9 RECEIVE 1

1 10 /proc/boot/procnto-smp-instr 10 RECEIVE 1

1 11 /proc/boot/procnto-smp-instr 11 RUNNING

1 12 /proc/boot/procnto-smp-instr 12 RECEIVE 1

2 1 proc/boot/kkissh kkissh REPLY 1

8195 1 proc/boot/pidin 1 REPLY 1For process 1, the kernel process, first these three threads:

1 1 /proc/boot/procnto-smp-instr idle_cpu_0 READY

1 2 /proc/boot/procnto-smp-instr ipi_cpu_0 INTR

1 3 /proc/boot/procnto-smp-instr clock_cpu_0 INTRI'm gonna go out on a limb and guess that the first one is the idle thread for CPU 0. (We first talked about the idle thread back in "Create a basic image".) It's in the state READY meaning it's ready to be placed on CPU 0 when it's the highest-priority thread that's ready to run on that CPU. How many CPUs does this system have?

/ # pidin syspage=header

Header size=0x000000f0, Total Size=0x00000910, Version=2.0, #Cpu=1, Type=4352Oh right, we said in the first article that we were going to set up a QEMU system with one CPU (-smp 1).

Just one CPU, so the fact that we're doing something when we run pidin means the idle thread is not the highest priority thread ready to run on that CPU.

But, there are 2 other threads with a name that ends with _cpu_0:

ipi_cpu_0, andclock_cpu_0

and they're both in state INTR, meaning they're Interrupt Service Threads (ISTs), and they're waiting for an interrupt. More on that when we cover interrupts, but, for now, I'll say this:

- Inter-processor interrupts (IPIs) are used by the kernel to initiate and coordinate activity across CPUs.

- The clock IST helps manage software timers (e.g.

timer_settime()). - The suffix

_cpu_Nmeans it's a per-CPU thread locked to CPUNonly.

Aside: Four CPUs

If we modify the QEMU command-line parameters to use -smp 4, so that QEMU will configure a system with 4 CPUs, here's what we get:

/ # pidin syspage=header

Header size=0x000000f0, Total Size=0x000009a0, Version=2.0, #Cpu=4, Type=4352

/ # pidin threads

pid tid name thread name STATE Blocked

1 1 /proc/boot/procnto-smp-instr idle_cpu_0 READY

1 2 /proc/boot/procnto-smp-instr idle_cpu_1 RUNNING

1 3 /proc/boot/procnto-smp-instr idle_cpu_2 READY

1 4 /proc/boot/procnto-smp-instr idle_cpu_3 RUNNING

1 5 /proc/boot/procnto-smp-instr ipi_cpu_0 INTR

1 6 /proc/boot/procnto-smp-instr ipi_cpu_1 INTR

1 7 /proc/boot/procnto-smp-instr ipi_cpu_2 INTR

1 8 /proc/boot/procnto-smp-instr ipi_cpu_3 INTR

1 9 /proc/boot/procnto-smp-instr clock_cpu_0 INTR

1 10 /proc/boot/procnto-smp-instr clock_cpu_1 INTR

1 11 /proc/boot/procnto-smp-instr clock_cpu_2 INTR

1 12 /proc/boot/procnto-smp-instr clock_cpu_3 INTR

...Looks like the idle threads are running on CPUs 1 and 3. i.e. on those CPUs, that CPU's idle thread was scheduled onto the CPU to tell that CPU, "Shhhhhh.".

More Kernel Process Threads

Moving on to the next threads in the kernel process:

1 4 /proc/boot/procnto-smp-instr sched_sporadic NANOSLEEP

1 5 /proc/boot/procnto-smp-instr thread_reaper SEM 0These are threads that help with the

Then the rest:

1 6 /proc/boot/procnto-smp-instr 6 RECEIVE 1

1 7 /proc/boot/procnto-smp-instr 7 RECEIVE 1

1 8 /proc/boot/procnto-smp-instr 8 RECEIVE 1

1 9 /proc/boot/procnto-smp-instr 9 RECEIVE 1

1 10 /proc/boot/procnto-smp-instr 10 RECEIVE 1

1 11 /proc/boot/procnto-smp-instr 11 RUNNING

1 12 /proc/boot/procnto-smp-instr 12 RECEIVE 1Most are RECEIVE-blocked. i.e. waiting to receive a message on a channel, specifically channel 1. So these are the threads in the kernel process's thread pool.

However, one of them is running. I'm going to guess that's the one that is helping pidin get information about the system.

Aside: What's In A Name?

Did you notice that the thread in our kkissh program has a name?

2 1 proc/boot/kkissh kkissh REPLY 1

^^^^^^i.e. the one-and-only thread in kkissh, i.e. process 2, thread 1, has a name, "kkissh". By default, a thread does not have a name. I added this code to kkissh:

pthread_setname_np(0, "kkissh");where:

pthread_setname_np()lets you set a thread's name,0means "set the name for this thread", the one that's calling this function (thread ids start at 1), and_npmeans "Although this function has the prefixpthread_, this is a non-portable function". QNX has it. Other OSs may not (but it looks like a lot do).- This is a naming convention POSIX recommends, although my grepping is failing me atm.

It can be helpful to give your threads a name to help identify what a thread is doing when looking at output from pidin. In this case, it added no value to the single-threaded kkissh program other than to demonstrate that setting a thread's name can be easily done.

Extra Aside: REPLY?

Why is the kkissh's one-and-only thread REPLY-blocked? To whom did it send a message (and from whom it has not yet received a reply)? The 1 on the very right means it's reply-blocked on a connection to process 1. If we run pidin with -v (verbose), we can get even more info:

/ # pidin -v threads

pid tid name thread name STATE Blocked

1 1 /proc/boot/procnto-smp-instr idle_cpu_0 READY

1 2 /proc/boot/procnto-smp-instr ipi_cpu_0 INTR

1 3 /proc/boot/procnto-smp-instr clock_cpu_0 INTR

1 4 /proc/boot/procnto-smp-instr sched_sporadic NANOSLEEP

1 5 /proc/boot/procnto-smp-instr thread_reaper SEM 0

1 6 /proc/boot/procnto-smp-instr 6 RUNNING

1 8 /proc/boot/procnto-smp-instr 8 RECEIVE 1

2 1 proc/boot/kkissh kkissh REPLY procnto(1) 0s-1-2s

3 1 proc/boot/pidin 1 REPLY procnto(1) 3-1-3si.e.

| Info | Description |

|---|---|

procnto(1) |

Process 1, aka procnto, aka the kernel process |

0s |

Client's connection id: i.e. side channel 0 to the kernel process |

1 |

Server channel: i.e. kernel process's public channel |

2s |

Server connection id (Ignore for now. Deeper topic) |

So kkissh has sent a message to the kernel process over its side channel connection to it. Well, at this point, with pidin running, the kkissh code (which isn't really very different from nkiss) is wait()ing for pidin to finish, so I'm gonna bet that wait() sends a message (MsgSend()) to the Process Manager server in the kernel process over the side channel, asking it to be notified when the process pidin terminates. When pidin terminates, the Process Manager will reply to the message.

Less Is More?

In the spirit of having a truly minimal system, e.g. we're configured to only have one CPU, and a minimal image config with a program that has a ridiculously-simple while(1) loop that we haughtily dare to call a "shell", I'm wondering if we need all those threads in the kernel process's thread pool. Can we get away with fewer?

First question is: Can the number of threads in the kernel process's thread pool be configured?

The documentation for procnto-smp-instr gives us the answer under "Environment variables:"

PROC_THREAD_POOL= low[,high[,max]]

Specify the configuration of procnto's thread pool. You must specify the low-water mark,

and you can optionally include the high-water mark and maximum number of threads.

If the values are invalid, they're ignored.

The default values are 3, 10, and 75, respectively.Now, this is an environment variable for the kernel process. How can we set an environment variable for it??

We saw in an earlier posting how we could set an environment variable for our nkiss program. We wanted to use posix_spawnp() to search for the program we're trying to run, and the docs for posix_spawnp() say they search the file system based on the environment variable PATH, so we modified our init script to launch nkiss to look like this:

PATH=/proc/boot /proc/boot/nkissEarlier in the image build file we have this where we specified procnto-smp-instr (with no command-line arguments):

[virtual=x86_64,multiboot] boot = {

startup-x86 -D8250

procnto-smp-instr

}Guess how we can set an environment variable for the kernel process:

[virtual=x86_64,multiboot] boot = {

startup-x86 -D8250

PROC_THREAD_POOL=1,1,1 procnto-smp-instr

}and now

/ # pidin threads

pid tid name thread name STATE Blocked

1 1 /proc/boot/procnto-smp-instr idle_cpu_0 READY

1 2 /proc/boot/procnto-smp-instr ipi_cpu_0 INTR

1 3 /proc/boot/procnto-smp-instr clock_cpu_0 INTR

1 4 /proc/boot/procnto-smp-instr sched_sporadic NANOSLEEP

1 5 /proc/boot/procnto-smp-instr thread_reaper SEM 0

1 6 /proc/boot/procnto-smp-instr 6 RECEIVE 1

1 7 /proc/boot/procnto-smp-instr 7 RUNNING

2 1 proc/boot/kkissh kkissh REPLY 1

3 1 proc/boot/pidin 1 REPLY 1Waaaaay fewer threads in the kernel process's thread pool now. Sleek!

But, there are 2 thread pool threads. We said we only wanted 1. Bigger story. And irrelevant because...

We must now ask ourselves: Is this sleek thread pool configuration a good idea? In general, no. No no no no no. It's fine for this experimental minimal system, where we're just "'new boot' goofin'" / just goofin' around, that's all!

For normal use, the default thread pool config is a good default.

Coming Up...

"quick detour", eh? That was not quick. Enough of this menagerie of detours.

Next time is malloc() and mmap().